Peter Drucker has been known as the “father of management.” Drucker’s management strategies recognized talent and rewarded it. He saw workers as assets and as part of a workplace community that deserved capital resources in order to accomplish ambitious goals that would reward employees and the company that they worked for with bigger profits that would enable bigger outcomes for everyone. The company could win and so could the worker. In The Practice of Management, Drucker wrote, “professional people should be given the incentive and recognition of professional status.” (1)

Drucker (1909-2005) lived a long life and in the 1990’s he noticed the importance of knowledge workers in a technology influenced economy. The idea of the knowledge worker went along with his earlier appreciation for talented workers. They were more specialized workers as technologies came to be a larger part of innovation in an information economy. He imagined that knowledge workers would gain more influence in the workplace in deciding how work would be done. They would gain more influence because only a knowledge worker would have the training, experience and know-how to accomplish the company’s goals. But in the twenty-first century, as production has been eclipsed by speculation in the financialized economy, knowledge workers have lost professional influence.

Jobs in America have been deskilling since the 1980’s. And many knowledge workers have lost their professional influence. There’s been deskilling in a variety of professions. For example, mandatory testing in public schools has led to deskilling in the profession of teaching. Instead of teachers structuring their curriculum to empower knowledge workers of the future in analysis and independent thinking, teachers have been expected to teach for tests that demonstrate proficiency in producing good test results. Students are supposed to excel in test taking (conforming to an external standard) instead of independent thinking. Doctors are expected to follow a diagnosis tree that proves that they follow along with standards of care set by diagnostic trees (or risk a mal-practice lawsuit) instead of basing their diagnosis on their own experience with patients. This can increase the number of billable tests and it can decrease the amount of time doctors spend with patients. Linking patient care with more federal programs may lead to further reduction of a doctor’s opportunity to act professionally by using his/her own judgement.

According to one source, deskilling has happened because of a surplus of workers and also because of new technologies. And deskilling shows a lack of coordination and cooperation between managers, workers and owners. Some industries with less cooperation between owners and workers have included jobs in public education, the Postal Service, the insurance industry, jobs in air traffic control, longshoring, and newspaper printing. Mobile capital also played a role, “The absence of national legislation which regulates capital mobility within and out of the United States has led to plant shutdowns and union membership losses.”(2)

“Golden handcuffs” express the idea that a person can get trapped in a job because starting over has too high a penalty. For example, too high a cost in retraining education or in health insurance fees or in the loss of pay, all happening under an economic system with high taxes. Economic instability can also make starting over too risky because demand can fall in any profession which was recently in greater demand. A small capital holder has finite resources for educational retraining.

Yet according to Peter Drucker, “You are responsible for allocating your life. Nobody else will do it for you….Effective self development must proceed along two parallel streams. One is improvement–to do better what you already do reasonably well. The second is change–to do something different. Both are essential.”(3) And the idea of “golden handcuffs,” doesn’t leave much room for doing something different. According to Hannah Arendt in The Human Condition, people’s jobs are an opportunity for self discovery. Inside our skills and accomplishments we discover new abilities and demonstrate our competency. We as doers are delighted by what we can achieve (4). Delighted accomplishment and self discovery are far from the idea of “golden handcuffs”! The recent increase in U.S. worker non-participation and recent losses in productivity may indicate too little incentive in the workplace to retain workers and incentivize the best work. Drucker would probably agree with the idea that a person’s delight in their work combined with capital rewards for excellence provide workers with performance incentives which can lead to better outcomes for everyone. And “golden handcuffs” just aren’t any kind of incentive that can encourage good work and the best outcomes.

(1) Peter F. Drucker, The Practice of Management, (Harper and Row, Publishers, U.S.A., 1954, first copyright), 154.

(2) Daniel B. Cornfield, ed., Workers, Managers, and Technological Change: Emerging Patterns of Labor Relations, (Plenum Press, New York, 1987), 346, 352.

(3) Peter F. Drucker, Managing the Non-Profit Organization: Principles and Practices, (Harper Business, Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 1990, 222, 223.

(4) Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1958), 175 translation from Latin: “For in every action what is primarily intended by the doer, whether he acts from natural necessity or out of free will, is the disclosure of his own image. Hence it comes about that every doer, in so far as he does, takes delight in doing…”

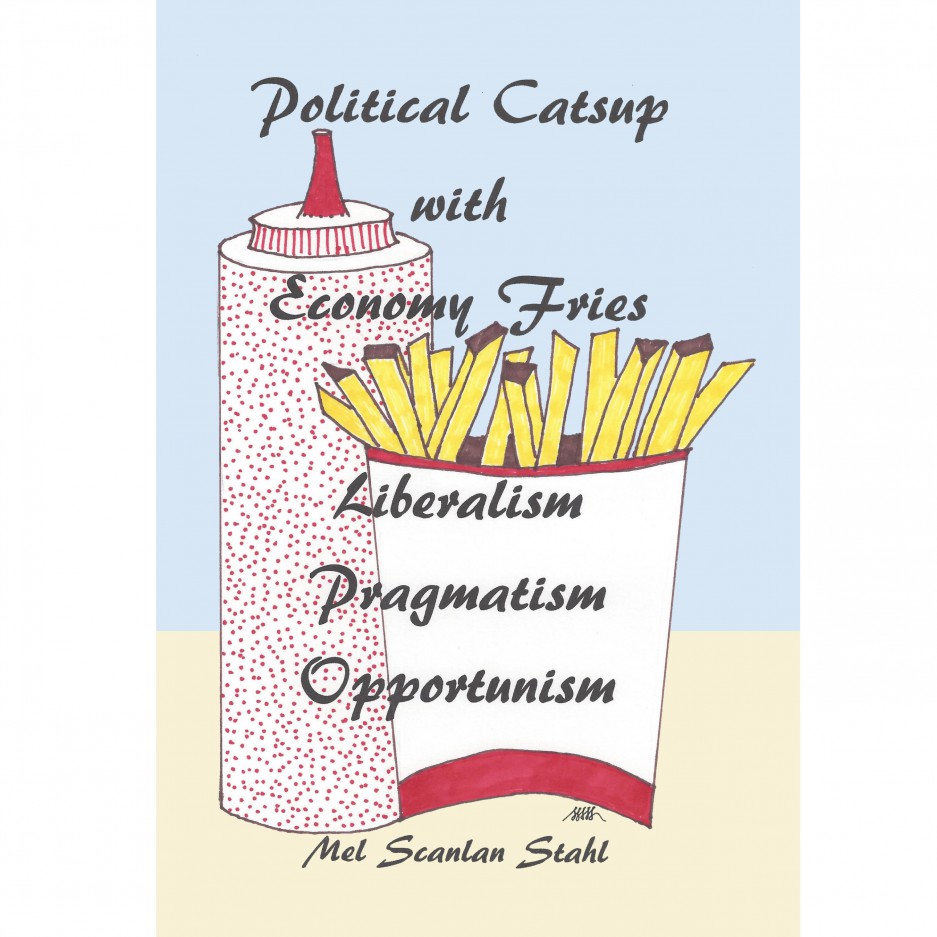

Buy a copy of Political Catsup with Economy Fries at Amazon.

Writings here are protected by fair use standards and copyrighted to Mel Scanlan Stahl. Please acknowledge me as the source whenever you use information in this blog. And please leave a comment.

Here’s a link to another person’s commentary regarding her job (an open letter she wrote to her CEO). It got her fired. It shows that the price structures in her life are completely out of line with what she can afford. It also shows an economy out of balance with supply and demand market forces. Zerohedge criticizes her for being unsympathetic to the corporation’s need to make a profit. When I read the letter it sounds to me like an episode from the Twilight Zone. But instead of the Twilight Zone, its just another day in the real American economy. I invite you to read Talia Jane’s open letter to her CEO. Here’s the Zerohedge link where I found the letter.